Introduction

In vitro fertilization (IVF) turned 45 this year. Once a fringe experiment, it’s now a standard medical service that has helped create more than ten million births worldwide. Yet IVF still depends on a biological bottleneck, human eggs. A woman’s supply is finite, and egg donation remains invasive, costly, and ethically complex. Now a new frontier in reproductive science, lab made human eggs, could someday remove that barrier entirely.

In an earlier post, I wrote about the potential of artificial wombs and how they might change the landscape of reproduction. Lab made human eggs sit on the same horizon. Both represent technologies that could shift reproductive control away from the limits of biology and toward systems that are designed, optimized, and eventually sharable.

Will it be possible to make eggs in the lab, just as IVF makes embryos? The idea, called in vitro gametogenesis (IVG), imagines a future where new eggs or sperm could be grown from ordinary body cells. It could transform fertility medicine and force society to rethink reproduction itself: who can have children, at what age, and with whose DNA.

That future is not science fiction anymore. In 2025, a team at Oregon Health and Science University, led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov, with lead authors Núria Martí-Gutierrez and Alexandra Mikhalchenko, reported an experimental step that brought IVG from concept to partial reality. In their recent Nature Communications paper, they showed that human cells could be pushed partway through egg formation—farther than anyone had gone before in creating lab made human eggs.

Background: Why Scientists Want to Create Lab Made Human Eggs

Eggs are scarce and delicate. Unlike sperm, they can’t be produced indefinitely, and retrieving them involves hormone injections and surgery. Age-related infertility, early menopause, and cancer treatments that destroy ovarian tissue all make fertility restoration difficult.

If scientists could produce lab made human eggs from skin or blood cells, they could, in theory, reverse infertility and expand reproductive possibilities. Couples who can’t produce their own eggs could have genetically related children. Same-sex couples could have children sharing DNA from both partners. Older adults or cancer survivors could become parents again using their own cells. They also open the door to gene editing to cure genetic diseases and potentially also for genetic enhancement.

These are profound possibilities, but they also raise profound questions. What happens when reproduction no longer depends on the body’s natural limits? How do we balance scientific potential with ethical restraint?

The Mitalipov Team’s Strategy to Create Lab Made Human Eggs

The Mitalipov team began with two ingredients: a donated human egg and a human skin cell. They removed the egg’s nucleus—the DNA-filled core—and replaced it with the nucleus from the skin cell. The egg’s surrounding material, called cytoplasm, acts as a natural reprogrammer: it contains the machinery that can reset DNA’s state.

Next, they nudged that nucleus to shed half of its chromosomes, the hallmark of egg formation. Afterward, they fertilized the reconstructed eggs with sperm and watched for early development. Of 82 reconstructed eggs, about nine percent reached the blastocyst stage, the earliest embryonic phase. None developed further. Most had too many or too few chromosomes, making them genetically unstable.

Even so, this showed that an adult cell’s DNA can, in rare cases, be reset enough for the first steps of embryonic growth. It’s a proof of principle, not a path to pregnancy, but it marks the first credible step toward viable lab made human eggs.

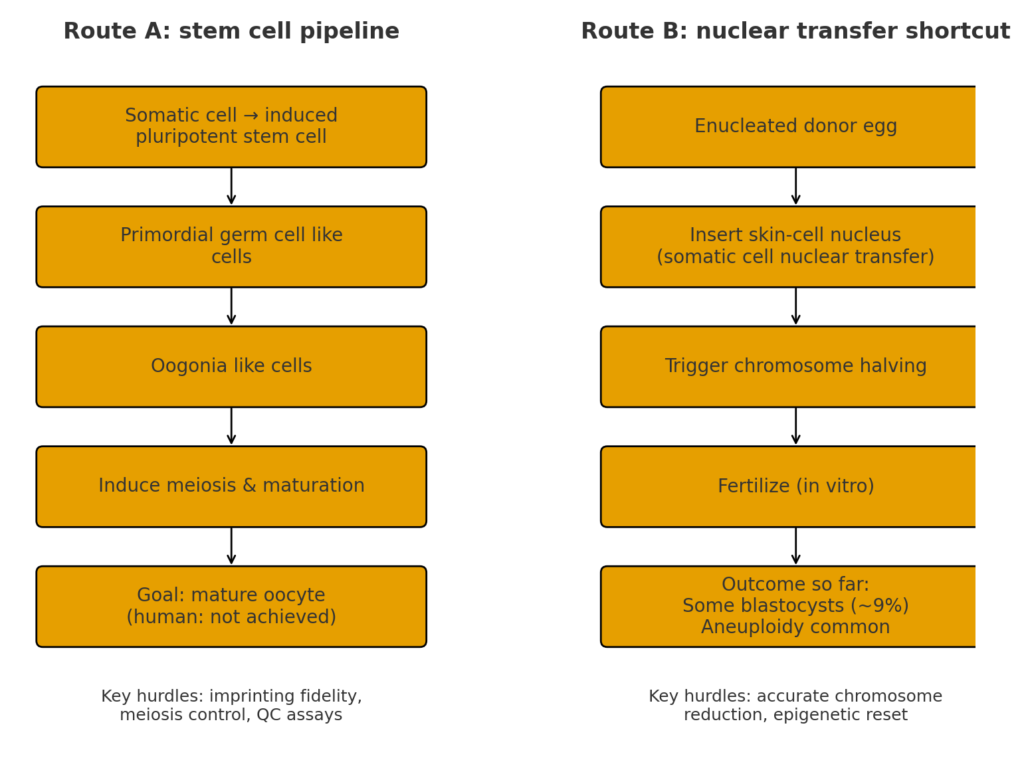

Two Routes to Lab Made Human Eggs

Researchers now see two main roads toward lab made human eggs.

1. The stem-cell route

This approach begins by turning a skin or blood cell into a pluripotent stem cell—a kind of blank cell that can become anything. Scientists then guide it through stages that mimic how eggs form naturally: germ cells → early egg precursors → mature eggs. In mice, this full journey has already succeeded, producing viable offspring. In humans, the later stages of meiosis, where chromosomes split and recombine, remain difficult to control.

2. The nuclear-transfer shortcut

OHSU uses this method. Instead of building a new egg from scratch, it uses a donated egg as a biochemical incubator. The nucleus from a skin cell is inserted into the egg, and the egg’s machinery tries to reprogram it. The challenge are forcing chromosomes to halve accurately, and resetting the DNA’s epigenetic marks—the chemical labels that control which genes turn on.

Why Lab Made Human Eggs Are Hard to Perfect

Meiosis control: Every chromosome must separate perfectly. Even a single mistake can halt development.

Epigenetic reprogramming: Each germ cell must erase and rebuild the chemical marks that govern development. So far, this process is inconsistent.

Quality control: The field still lacks an agreed definition of “functional” lab made human eggs. Tests for chromosome number, imprinting accuracy, and mitochondrial health are being developed but not yet standardized.

Why Lab Made Human Eggs Matter

If these technical barriers can be overcome, lab made human eggs could transform reproductive medicine. They offer a way to restore fertility after cancer treatment or early menopause, enable genetic parenthood for same-sex couples, reduce dependence on invasive egg donation, allow DNA editing to cure genetic diseases, and potentially for genetic enhancement.

But this promise comes with a responsibility for caution. Biology is not infinitely forgiving. Each step, chromosome sorting, reprogramming, fertilization, must be engineered to near perfection before anyone considers clinical use.

Timelines and Hype

Some enthusiasts predict lab made human eggs within a decade. The work of the Mitalipov team suggests a longer arc. Progress is real but fragile. Expect years of incremental improvement before anyone can safely call this reproductive medicine rather than experimental biology.

Rules and Ethics Catching Up

The International Society for Stem Cell Research updated its 2025 guidelines to address embryo-like research and IVG. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics issued a policy brief highlighting questions of consent, regulation, and cross-border oversight. Governments will likely draw on both as they craft laws for this new frontier of lab made human eggs and other reproductive innovations.

Key issues still demand public discussion:

- Who can donate eggs for research?

- How can labs prevent misuse of personal cells to create gametes without consent?

- What benchmarks must define a “safe” lab made human egg?

Lessons from the Animal World

Before humans, mice have already shown what is technically possible. In 2012, Japanese scientists produced healthy baby mice entirely from lab-created eggs and lab-created sperm, both derived from stem cells. This was the first time the complete cycle of in vitro gametogenesis, i.e. making eggs and sperm outside the body, fertilizing them, and producing living offspring, had been achieved in a mammal.

Later experiments went even further. In one study, scientists produced mice with two genetic mothers by manipulating the epigenetic marks that normally distinguish maternal and paternal DNA. Together, these milestones demonstrate that both eggs sperm can, in principle, be reconstituted from ordinary cells.

These experiments prove that the logic of IVG works in animals. But they also highlight the enormous gap between species. Human egg and sperm development are slower, more complex, and far more sensitive to errors in chromosome handling and imprinting. The mouse work shows what’s possible, but not yet what’s safe for creating lab made human eggs.

The Next Frontier: Lab-Made Sperm

While most attention focuses on eggs, the same principles could apply to sperm. Early experiments in mice and human cell cultures have already produced immature sperm-like cells from stem cells. In mice, some of these sperm-like cells have successfully fertilized eggs and produced live offspring, proving that the concept works in principle.

If that becomes possible in humans, it would complete the reproductive circuit—both egg and sperm derived from ordinary cells. That could open pathways for same-sex reproduction, fertility restoration after testicular failure, and possibly gene editing. Each scenario raises deep questions about identity, inheritance, and what counts as “natural” reproduction.

The same caution applies here as with lab made human eggs: success will depend on error-free meiosis, faithful imprinting, and exhaustive testing before any clinical use. But scientifically, the groundwork has already begun.

My Take

The Mitalipov team’s breakthrough is both exhilarating and sobering. It proves that egg cytoplasm can reprogram DNA, but also that nature guards reproduction with unforgiving precision. The road from proof to practice will require meticulous engineering and transparent oversight.

Handled responsibly, lab made human eggs could become the next great chapter in the story that began with IVF, turning reproductive biology into something we can repair, and maybe one day redesign.

Your Thoughts About Lab Made Human Eggs?

I’m curious where you land on this. Lab made human eggs could reshape fertility care, expand who can become a genetic parent, and open the door to human germline engineering. At the same time, it raises complicated questions about safety, identity, and how far we want this technology to go.

Some questions to ponder:

-

Would you support clinical use once the science is proven safe?

-

How should labs guard against creating gametes from someone’s cells without consent?

-

Should age limits apply if eggs and sperm can be made from any cell?

-

How do you feel about the possibility of same-sex genetic reproduction?

- Would it be acceptable to genetically edit these gametes to cure genetic diseases? For genetic enhancement?

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments. I read every one, and your feedback helps shape future Bleeding Edge Biology posts.

Be sure to visit bleedingedgebiology.com next week for another “bleeding edge” topic!

Recommended by Bleeding Edge Biology

Curious to learn more about lab made human eggs and the science reshaping reproduction? The following articles, talks, and documentaries explore the biology, ethics, and policy debates surrounding in vitro gametogenesis. These are hand-picked references offering multiple perspectives on how lab-grown eggs, sperm, and embryo technologies are redefining fertility and identity.

Primary Scientific Papers

-

Martí Gutierrez, N., Mikhalchenko, A., et al. (2025). “Induction of experimental cell division to generate cells with reduced chromosome ploidy.” Nature Communications, 16, 8340.

— Researchers used somatic cell nuclear transfer and a novel reductive division method (“mitomeiosis”) to convert human skin-cell nuclei inside enucleated eggs, achieving partial chromosome reduction and early embryo formation—an important step toward lab made human eggs. -

Hayashi, K. et al. (2021). “Reconstitution of the entire cycle of the mouse female germ line in vitro.” Science, 374(6563), 42–48. — Demonstrates complete IVG in mice, leading to live births.

-

Nayernia, K. et al. (2006). “In vitro-derived sperm from mouse embryonic stem cells fertilize eggs and produce viable offspring.” Developmental Cell, 11(1), 125-132. — First demonstration that sperm derived from stem cells in vitro can produce viable mice.

-

Sato, T. et al. (2011). “In vitro production of functional sperm in cultured neonatal mouse testes.” Nature Communications, 2, 472. — Advances in lab-derived sperm via testis-tissue organ culture.

-

Kono, T. et al. (2004). “Birth of parthenogenetic mice that can develop to adulthood.” Nature, 428, 860-864. — Two-mother offspring created from reprogrammed female cells in a mammalian system.

Articles & Reviews

- Stem Cell-Derived Gametes: What to Expect When Expecting Their Clinical Introduction —

- de Bruin et al. (2025) Human Reproduction, 40(9): 1605-1615 Academic review on anticipated risks, follow-up studies, and clinical implications.

-

Modelling In Vitro Gametogenesis Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells —

Romualdez-Tan, M. V. (2023). Cell Regeneration, 12(1): 33.

Covers recent technical advances and remaining gaps in creating germ cells from pluripotent stem cells. -

Research Advances in Gametogenesis and Embryogenesis Using Pluripotent Stem Cells —

Luka, M., & Yu, Y. (2022). Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 9: 801468.

A detailed technical review of how stem-cell models are illuminating gamete and embryo development in vitro. -

Anticipating In Vitro Gametogenesis: Hopes and Concerns for IVG —

Le Goff, A., Hein, R. J., Hart, A. N., Roberson, I., & Landecker, H. L. (2024). Stem Cell Reports, 19: 933–945.

Stakeholder views on IVG, with perspectives from LGBTQ+ communities and concerns about safety and access. -

Is There a Valid Ethical Objection to the Clinical Use of In Vitro-Derived Gametes? —

Galea, K. (2021). Reproduction & Fertility, 2(4): S5–S8.

Explores the ethics of IVG, separating technical concerns from philosophical objections.

Policy & Ethics

- Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2025). In Vitro Gametogenesis: A Review of Ethical and Policy Questions. — Policy briefing offering a clear, practical overview of ethical, legal and social issues raised by IVG.

- The Regulatory Landscape for In Vitro Gametogenesis —

WCG Clinical Insights (2025).— Overview of how regulators worldwide are reacting to advances in IVG and what future frameworks might look like. - Ethics Talk: Discussing Ethics with Fertility Treatment Clients —

An AMA Journal of Ethics podcast featuring a clinician-led conversation about ethical and regulatory dilemmas in fertility treatment.

Talks & Video Resources

- Jennifer Doudna: How CRISPR Lets Us Edit Our DNA — Contextualizes the gene-editing tools behind next-generation reproductive science.

- Marcy Darnovsky: Use Gene Editing to Treat Patients, Not Design Babies — An ethicist’s sharp take on gene editing and reproductive biotech.

- Get Into Your Genes (TED Playlist) — Curated talks on gene editing, genome technology, and reproductive biology.

- The Harsh Reality of Being an IVF Baby — Documentary-style video exploring lived experiences of IVF-conceived individuals.

Documentaries / Series

- Human Nature (2019) — Explores CRISPR, gene editing, and what it means for humanity’s future.

- Unnatural Selection (Netflix, 2019) — Series on genetic engineering, biohacking, and assisted reproduction.

- Make People Better (2022) — Explores the first gene-edited babies case; essential viewing for ethical context.

Podcasts

- Ethics Talk: Discussing Ethics with Fertility Treatment Clients — AMA Journal of Ethics podcast on ethical and regulatory issues in assisted reproduction. Journal of Ethics

- Reproductive Technologies and Feminist Research (The Good Robot Podcast) — Episode exploring reproductive tech through feminist science studies.

- Episode 145: IVF, Part 3: Industry (This Podcast Will Kill You) — Looks at the business, science, and future commercial landscape of IVF-related technologies.