Introduction: A Planet on the Brink

Assisted Migration: A Bold but Necessary Solution

I used to believe conservation meant protecting species where they already lived — keeping forests, deserts, and wetlands intact so nature could heal itself. But after years of following the science, I’ve had to let go of that idea. In a world changing this fast, assisted migration — moving species to entirely new habitats — may be the only way to keep some of them alive.

Earth is losing species faster than at any time since the dinosaurs went extinct. Entire ecosystems are unraveling under the combined pressure of habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change. The Sixth Mass Extinction isn’t some distant threat — it’s happening right now.

Some species are trying to keep up by shifting their ranges, searching for cooler temperatures or more reliable rainfall. But the climate is moving faster than many species can follow. A redwood forest can’t uproot itself and migrate north. A Joshua tree can’t escape the Mojave heat. Without direct intervention, they’ll disappear.

For decades, the idea of moving species beyond their native ranges was seen as too risky. Relocated species could become invasive, fail to adapt, or disrupt ecosystems. But at this point, the bigger risk is doing nothing. The places species evolved to thrive no longer exist as they once did — and they won’t return.

If species can’t survive where they are, what choice do we have? Let them vanish? That’s exactly what will happen if we refuse to act.

The Controversy

Critics argue that moving species could cause unintended consequences, but let’s be honest—climate change is already causing unintended consequences. Wildfires are wiping out forests that stood for thousands of years. Coral reefs are bleaching beyond recovery. Species that evolved over millennia are vanishing in the span of a few decades.

Assisted migration comes with risks, but standing by while ecosystems unravel guarantees disaster. We can debate the risks all day, but for many species, assisted migration is the only real alternative to extinction.

This post will explore the science, the risks, and the success stories. But I’ll be clear from the start: We should be moving species. We should be protecting ecosystems. We should be using every tool available to keep life on this planet from collapsing.

What is Assisted Migration?

Conservation has long focused on protecting species where they already live. National parks, wildlife reserves, and habitat restoration efforts all operate under the assumption that if we stop destroying ecosystems, nature will recover on its own. That assumption no longer holds. Climate change is rewriting the rules, and many species are stranded in places that no longer support them.

Assisted migration is a radical departure from traditional conservation. Instead of trying to keep species in their historical ranges, it helps them move to where they can survive in the future. Scientists, conservationists, and even private landowners are relocating species beyond their natural boundaries to get ahead of climate collapse.

This approach doesn’t rely on guesswork or blind experimentation. Scientists base relocation decisions on climate modeling, species biology, and ecological research, choosing new habitats with care. The goal extends beyond saving individual species to preventing entire ecosystems from unraveling.

Three Types of Assisted Migration

Not all assisted migration efforts follow the same approach. Some involve subtle shifts, while others push species far beyond their historical limits. Conservationists generally classify assisted migration into three categories:

- Assisted Population Expansion – Moving a species within its current range to restore lost populations or help it reach suitable areas.

- Assisted Colonization – Relocating a species outside of its historical range when its current habitat is no longer viable.

- Ecosystem Translocation – Moving entire ecological communities, including plants, animals, fungi, and microbes, to create a fully functional system in a new location.

The Sixth Mass Extinction and the Need for Assisted Migration

Species have always come and gone. Over Earth’s history, five mass extinctions wiped out huge portions of life, from the Great Dying 250 million years ago to the asteroid that ended the dinosaurs. But unlike those events—caused by volcanic eruptions, climate shifts, or cosmic impacts—the current extinction crisis has a single cause: us.

Scientists estimate that species are disappearing 1,000 times faster than the natural background rate. Entire ecosystems are unraveling in real time. Coral reefs are bleaching, amphibians are vanishing, and forests are burning faster than they can regenerate. For some species, there’s no way out.

Species That Can’t Move Fast Enough

Not every species can migrate to escape climate change. Some are physically incapable of moving quickly enough, while others are boxed in by geography. Without human intervention, many are on a collision course with extinction.

Take the American pika, a small, rabbit-like mammal that thrives in cool, rocky habitats in the western United States. Pikas are highly sensitive to heat. When temperatures rise above their tolerance, they retreat higher up mountain slopes in search of cooler conditions. But they can only go so far. Many pika populations have already reached the peaks of their ranges, with nowhere left to escape the warming climate. In some areas, entire colonies have disappeared, wiped out by heat stress and habitat loss.

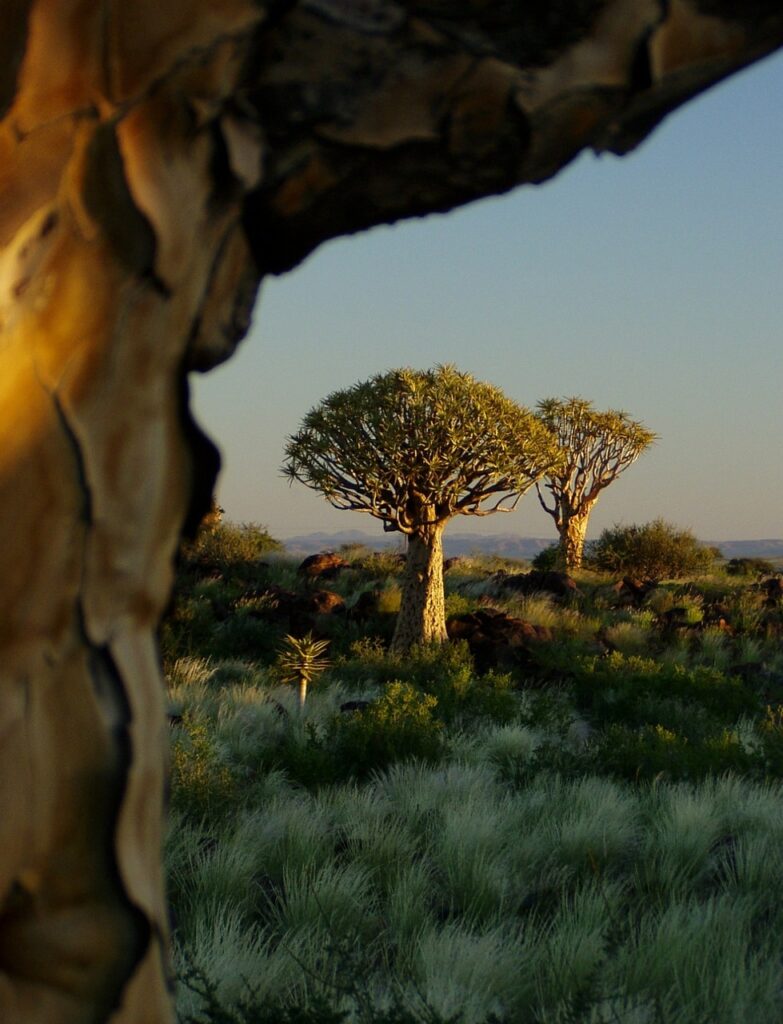

The quiver tree, a striking aloe native to Namibia and South Africa, faces a different challenge. Unlike animals that can move in search of cooler ground, trees are stuck where they grow, and their seeds must establish new populations elsewhere. The quiver tree has adapted to extreme conditions, storing water in its trunk to survive prolonged droughts. But even this resilience has limits. Some of the oldest quiver trees are dying where they stand, and younger trees aren’t replacing them fast enough. Climate models suggest that large portions of their range could become uninhabitable within decades.

Then there’s the Atlantic puffin, which depends on cold-water fish like sand eels to feed its chicks. As ocean temperatures rise, those fish are moving to deeper, cooler waters, leaving puffin colonies starving. On islands off the coast of Maine, puffin chicks are dying in their nests as their parents struggle to find enough food. Unlike land animals, puffins can’t simply shift their breeding sites northward—they need specific islands, free from predators, with access to the right fish at the right time of year. As climate change disrupts that balance, many puffin colonies are collapsing.

These species, like countless others, evolved within stable ecosystems that no longer exist. In the past, they had thousands of years to adapt to slow climate shifts. Today, they have decades—or less.

Natural Migration Isn’t Enough

Some say species will figure it out on their own. That’s not how it’s working. For some species, natural migration is breaking down because the paths they once followed no longer exist.

Animals that once roamed freely now run into highways, cities, and endless farmland. Routes that once allowed species to shift across thousands of miles are now cut off by human development. Even when movement is possible, climate change is moving faster than they can. Scientists tracking species shifts have found that plants and animals are heading toward the poles and up mountains at rates never seen before. But in most cases, it’s still not fast enough.

Most species need to move at least 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) per year to stay within suitable climate zones. Fast-moving species like birds and some mammals might manage this—if they have clear migration corridors. But trees, desert plants, and slow-moving wildlife have no chance. Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) grow just 1.5 to 3 inches per year, and their seeds spread at a rate of only 3 to 7 feet per year. This is nowhere near fast enough to outrun rising temperatures in the Mojave Desert.

Coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) face the same issue. While individual trees grow quickly, their seeds don’t travel far and often land in landscapes that are already too hot or too dry to support them.

Even if a species could move, it’s never moving alone. A forest depends on more than its trees. Fungi, pollinators, microbes, and countless interdependent species work together to keep the entire system alive. Coral reefs function the same way. Beneath the surface, thousands of species—from tiny polyps to grazing fish—build and maintain the reef’s structure. When one piece breaks down, the whole system starts to unravel.

This is why assisted migration matters. Species that could survive in new habitats will never reach them on their own. Moving them gives them a path to survival they no longer have on their own.

Why Assisted Migration is the Right Move

I understand why people hesitate. Moving species feels like interference. But let’s be honest: we’re already interfering. We’ve altered the atmosphere, fragmented habitats, and pushed thousands of species to the brink.

Assisted migration is a response to the damage we’ve already done—a way to help species survive the conditions we’ve forced on them. We’ve stacked the deck against them. This is one way to even the odds.

The reality is, assisted migration is already happening. Scientists, conservation groups, and even private citizens are relocating species to safer ground. In the next section, I’ll go through some of the most promising—and controversial—efforts to help life move toward a future it can survive.

Case Studies of Assisted Migration in Action

Some of the most ambitious assisted migration projects are already underway. Some of these efforts are experimental, while others are full-scale conservation projects aimed at preventing ecosystem collapse.

Western Swamp Tortoise: Australia’s Climate Refugee

The western swamp tortoise (Pseudemydura umbrina) is the first endangered vertebrate to be deliberately relocated due to climate change. Once thought extinct, this critically endangered species from southwestern Australia was rediscovered in 1954. By the early 2000s, its last remaining habitat held only captive-bred tortoises, with climate change making natural recovery unlikely.

In 2016, 24 captive-raised juveniles were released 300 kilometers south of their native range, where cooler, wetter conditions could give them a better future. Unlike controversial relocation efforts elsewhere, this move followed years of planning and research, with cautiously positive results published in 2020.

A second release followed in 2022, this time in Scott National Park, led by Nicola Mitchell from the University of Western Australia. Mitchell calls the project an ethical responsibility, arguing that doing nothing would doom the species to extinction.

The project highlights the larger debate over how to save species in a warming world. Mark Schwartz of UC Davis doubts mass relocations could solve the global biodiversity crisis but agrees they’re more acceptable than genetically modifying species to survive climate change. Releases continued into 2023, as researchers refine methods and monitor whether assisted migration can truly offer the species a future.

Moving Redwood and Sequoia Forests Northward

California’s coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) and giant sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum) have endured for millennia, surviving Ice Ages, wildfires, and droughts thanks to their thick bark, towering canopies, and natural resistance to pests. But megafires, prolonged drought, and rising temperatures are now outpacing even their legendary resilience.

For decades, redwoods and sequoias have grown outside their native range, thriving in cities like Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, where cooler, wetter conditions help them flourish. Now, groups like PropagationNation are supporting efforts to plant new groves in Oregon, Washington, and even Canada, creating potential climate refuges for these iconic trees.

These new plantings could offer benefits well beyond preserving redwoods themselves. Many Canadian forests are already in crisis, hammered by drought, bark beetles, and record-breaking wildfires. Vast sections of British Columbia’s interior forests now stand dead or have burned so intensely they may never recover naturally. Redwoods’ natural resistance to pests and fire, combined with their ability to thrive in wetter northern climates, could help restore resilience to these battered landscapes.

The idea isn’t far-fetched. In the late 2000s, British Columbia officially approved the assisted migration of Western Larch 1,000 kilometers north to keep pace with climate shifts. In 2022, a Canadian Forestry Service report proposed that narrow strips of Vancouver Island already provide suitable habitat for coast redwoods, based on successful test plantings and studies of redwood paleogeography.

That ancient history matters. Fossil evidence confirms that redwoods, including Metasequoia, once thrived across much of what’s now Canada, from Alberta to the Arctic Archipelago. Millions of years ago, redwood forests even covered parts of Axel Heiberg Island, showing that much of Canada’s climate once supported these species.

Some ecologists warn that introducing redwoods could disrupt native ecosystems, but others argue that doing nothing risks losing both redwoods and the carbon-storing forests they could help rebuild. With so much forest already gone or dying, planting redwoods and sequoias in carefully chosen northern sites could offer both the trees—and Canada’s struggling forests—a second chance.

Camp Fire Reforestation Plan: Future-Proofing California’s Forests

The 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, was the state’s deadliest wildfire, destroying over 18,000 structures and claiming 85 lives. In response, the USDA Forest Service, under the guidance of Jianwei Zhang, is exploring reforestation strategies that enhance future forest resilience.

Specific details of the reforestation plan are not publicly available. However, climate-adaptive strategies often involve planting a diverse mix of tree species suited to anticipated future conditions. Species such as Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) are known for their drought tolerance and adaptability, making them potential candidates for such efforts.

Rather than simply replacing what was lost, this strategy aims to create forests that will thrive in the climate of 2050, not 1950. By selecting trees that are more heat- and drought-resistant, the project seeks to build forests that can better withstand future wildfires and long-term climate shifts. While restoring the landscape will take decades, these efforts lay the foundation for forests that can survive and sustain biodiversity in a rapidly changing world.

Joshua Tree Conservation Efforts

The Joshua tree, an icon of the Mojave Desert, may not survive the coming decades. Climate models predict that 90% of its habitat could disappear by 2100, as rising temperatures push conditions beyond what the species can tolerate.

There have been discussions and proposals regarding the assisted migration of Joshua trees (Yucca brevifolia) to counteract the adverse effects of climate change on their natural habitat. The National Park Service has highlighted the importance of assisted migration for the western Joshua tree. They emphasize relocating seeds, fruits, or even mature trees to areas projected to remain suitable under future climate scenarios, acknowledging that climate change may outpace the species’ natural ability to migrate.

Additionally, the Mojave Desert Land Trust has been proactive in conserving Joshua tree seeds. Their seed bank initiative aims to preserve genetic diversity and support future restoration projects. While they do not explicitly advocate for assisted migration, they recognize that having a repository of seeds could be invaluable if relocation becomes necessary to ensure the species’ survival.

However, although assisted migration has been proposed, it is important to note that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s “Western Joshua Tree Conservation Plan” does not currently provide specific guidelines for implementing assisted migration, citing insufficient research on the genetic and ecological implications. Future amendments to the plan may address these considerations as more data becomes available.

Los Angeles Urban Reforestation

Extreme heat, prolonged drought, and recent wildfires have wiped out vast sections of the city’s tree canopy, leaving neighborhoods exposed to rising temperatures and worsening air quality.

In response, groups like TreePeople are taking a climate-adaptive approach to urban reforestation, selecting drought- and fire-resistant tree species better suited to the conditions Los Angeles will face in the coming decades. This is a form of assisted migration, even if the trees aren’t moving far.

Urban forests provide critical ecosystem services—they cool neighborhoods, improve air quality, reduce energy use, and support biodiversity. Planting trees that can survive and thrive in a more extreme climate is a climate adaptation strategy designed to keep those benefits intact for future generations.

Urban reforestation efforts in Los Angeles also highlight the importance of choosing the right species. Iconic but highly flammable palm trees, long associated with the city, offer little shade and accelerate fire spread. Replacing them with native, drought-tolerant, and fire-resistant species could help protect both people and ecosystems.

Whether in wildlands or urban neighborhoods, assisted migration is increasingly part of the toolkit for adapting to climate change. The forests that once grew here may not survive the future, but with careful species selection and community involvement, new forests can be planted that are ready for the world ahead.

Torreya Guardians: A Citizen-Led Experiment in Species Relocation

Not all assisted migration efforts are government-run. In one of the most controversial examples, a group of citizen scientists known as the Torreya Guardians has taken conservation into their own hands.

Led by Connie Barlow and influenced by the late ecologist Paul S. Martin, the group has been moving the endangered Florida torreya tree to cooler regions, arguing that the species has no chance of survival in its native range.

Critics say this sets a dangerous precedent—relocating a species without official oversight could lead to unintended ecological consequences. But the Torreya Guardians argue that the alternative is extinction. If we wait for bureaucratic approval, it may be too late.

Saving Monarch Butterflies by Moving Their Habitat

In 2024, scientists reported positive results from a dual-species assisted migration project near Mexico City. Researchers planted sacred fir (Abies religiosa), the tree monarch butterflies rely on for winter shelter, on the slopes of an extinct volcano about 75 kilometers from the monarchs’ current sanctuary. The new site sits at higher elevations, where cooler temperatures could offer a more reliable climate refuge as warming disrupts lower forests.

Before the firs could take hold, researchers planted Baccharis conferta, a native shrub that shields young seedlings from frost and drought. This paired planting strategy, moving both habitat and species together, is far more complex than typical single-species assisted migration projects.

A 2024 study coauthored by thirteen scientists found that sacred fir can survive and establish between 3,600 and 3,800 meters, above the species’ current range. With time, these new forests could become a climate-safe overwintering site for monarchs.

Lead researcher Cuauhtémoc Sáenz-Romero noted that monarchs have already been seen forming new colonies in cooler areas of Nevado de Toluca, close to the test plantings. That suggests monarchs are already seeking higher, colder winter sites. If the transplanted firs thrive, the butterflies could naturally adopt the new habitat when the trees mature.

This project stands out for linking habitat creation with species survival, offering a rare example of how assisted migration could help whole ecosystems shift, not just individual species.

Coral Reefs: Transplanting Heat-Resistant Corals

Rising ocean temperatures are wiping out coral reefs worldwide, leaving them with little time to recover. Scientists are now exploring the assisted migration of heat-tolerant corals from the Red Sea, particularly species like Porites lobata, Stylophora pistillata, and Pocillopora verrucosa, to areas where native reefs are declining. The Red Sea’s corals, especially those from the Gulf of Aqaba and Arabian Gulf, have demonstrated exceptional thermal resilience, tolerating temperatures significantly higher than most other coral populations.

Researchers are assessing the feasibility of relocating these corals to cooler waters within the Indo-Pacific region, where coral degradation is severe. These locations could benefit from the introduction of thermally resilient corals to bolster their long-term survival. However, challenges such as ecological compatibility, genetic integration, and long-term monitoring remain critical concerns. If successful, assisted migration could offer a new tool for coral conservation in the face of accelerating climate change.

The Benefits of Assisted Migration

Moving species to new habitats was once considered too risky to attempt. But climate change is already disrupting ecosystems, driving extinctions, and weakening natural systems that support life.

Preventing Extinction Before It’s Too Late

For some species, there is nowhere left to go. The Bristlecone pine, one of the longest-lived trees on Earth, has survived for thousands of years in the high-altitude deserts of the western United States. Now, warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are making parts of its range uninhabitable.

The same is happening to the white lemuroid possum in Australia, which depends on the cool, misty conditions of mountain rainforests. Rising heat has wiped out entire populations, and without intervention, it could soon disappear.

By relocating species to more stable climates, conservationists can stop extinctions before they happen. Keeping them where they are is not an option.

Protecting the Ecosystems That Support Life

Ecosystems rely on keystone species to maintain balance. If those species vanish, the damage spreads. The mangrove forests of Southeast Asia provide storm protection, prevent erosion, and create nurseries for marine life. As sea levels rise, many mangrove populations are trapped between encroaching saltwater and human development. Some conservationists are working to establish new mangrove forests in areas where they will be able to migrate inland.

The Kakapo, a flightless parrot of New Zealand, is another example. It has been relocated to offshore islands to escape invasive predators, and now researchers are considering moving some populations even farther as climate change shifts food availability. The effort to keep these birds alive is also an effort to maintain the delicate ecosystems that evolved with them.

Helping Species Keep Up with a Changing World

Climate zones are shifting faster than many species can migrate. In the past, natural movement let plants and animals follow changing conditions over centuries. But today, highways, cities, and farmland block many migration routes. Species that could once move gradually across continents are now pinned in place, even as the climate around them changes too quickly for them to adapt.

That’s why some species already pushed to their limits are being relocated ahead of climate collapse. In Australia, scientists have moved western swamp tortoises over 300 kilometers south to cooler wetlands, because their original habitat is drying out faster than they can adapt. In Mexico, researchers are planting sacred fir trees at higher elevations to create a future overwintering forest for monarch butterflies, knowing the lower-elevation forests may become too warm. And in the southeastern U.S., the Torreya Guardians, a citizen-led group, have been planting Florida torreya trees in cooler parts of the Appalachian foothills, hoping to give the critically endangered tree a foothold in a climate zone it can tolerate.

These projects highlight a growing reality: without help, some species simply won’t be able to move fast enough to survive. Assisted migration isn’t just about saving species—it’s about giving life the room to shift and adapt in a world that humans have already changed.

Strengthening Urban and Agricultural Resilience

As the climate changes, cities and farms are already experimenting with species that can withstand extreme conditions. In some regions, agriculture is being transformed by shifting plant varieties that have been cultivated for centuries.

The tepary bean, a drought-resistant crop domesticated by Indigenous farmers in the American Southwest, is being reintroduced to areas struggling with water shortages. This heat-tolerant legume could replace more water-intensive crops as arid conditions expand.

In urban areas, reforestation efforts are adapting to changing climates. In Melbourne, Australia, city planners have begun planting species from drier regions in preparation for hotter summers and declining rainfall. The goal is to create urban forests that can survive the next century, rather than trying to preserve a tree population suited to past conditions.

The Risks and Ethical Dilemmas of Assisted Migration

Assisted migration is a necessary response to climate change, but it is not without risks. Moving species to new locations creates ecological uncertainties, and conservationists must weigh the potential benefits against unintended consequences. Some worry that relocating species could lead to invasiveness, genetic disruption, or ecosystem imbalance. Others argue that intervention crosses ethical boundaries—that humans should not decide which species get saved and which do not.

The debate is important, but it should not become an excuse for inaction. Every conservation strategy carries risks, including doing nothing. The challenge is determining when, where, and how to move species in ways that minimize harm while maximizing survival.

Could Assisted Migration Create New Ecological Problems?

One of the biggest concerns is the possibility of introduced species becoming invasive. History offers plenty of cautionary tales. The cane toad, introduced to Australia in the 1930s to control agricultural pests, spread rapidly and became a major problem, outcompeting native species and poisoning predators. The European starling, released in North America in the 19th century, displaced native birds and disrupted ecosystems.

Critics worry that species moved through assisted migration could outcompete local plants and animals, introduce new diseases, or disrupt delicate food webs. If a species thrives too well in its new environment, it could shift from being a conservation success to an ecological disaster.

Careful planning helps reduce this risk. Unlike past species introductions, which often ignored ecosystem consequences, modern assisted migration projects use ecological modeling to predict potential impacts. Scientists assess whether a species has invasive traits, how it interacts with other organisms, and whether its introduction could cause harm. Many proposed relocations involve species already struggling to survive—ones that are unlikely to spread aggressively in new environments.

For example, the Florida torreya is so endangered that even with relocation, its survival remains uncertain. The species is not expected to become dominant over native plants in its new range. Similarly, monarch overwintering trees are being relocated within ecosystems that already support them, minimizing disruption.

Will Relocated Species Survive in Their New Environments?

Even when assisted migration avoids invasive species risks, there’s no guarantee relocated species will thrive. Climate projections offer guidance, but nature rarely follows a script. A species might struggle if conditions shift in unexpected ways — or if key factors, like pollinators, symbiotic species, or critical soil microbes, are missing.

The western larch relocation experiment in Canada highlights this uncertainty. Scientists moved seedlings northward, expecting warmer temperatures to benefit them. But growth varied widely depending on local soil conditions, moisture levels, and unpredictable climate swings. Some populations thrived, while others faltered.

On top of that, many species — especially rare ones — lack detailed climate and habitat data. That makes it hard to predict the best future locations or how species will interact with unfamiliar plants, animals, and microbes. Sometimes, the biggest threat at a new site isn’t the climate at all, but disease, predators, or ongoing habitat loss. And if too many individuals are removed from the source population, it could weaken that population’s survival chances.

Genetic risks come into play too. Assisted migration often involves mixing individuals from different populations to boost genetic diversity. This can increase resilience — but it can also dilute locally adapted traits, reducing a species’ ability to cope with specific environmental pressures.

Conservationists try to manage these risks by using genetically diverse seed stocks, spreading relocation efforts across multiple sites, and combining ecological modeling with long-term monitoring. Still, there’s no simple formula for success — just a balancing act between intervention and uncertainty.

Are Humans Playing God?

Some critics argue that assisted migration crosses an ethical line—that humans should not interfere in species movements at such a large scale. There is an inherent subjectivity in deciding which species to save and which to leave behind. Should resources go toward preserving charismatic species like the monarch butterfly, or toward less-known but equally important organisms like soil microbes and fungi?

This debate mirrors long-standing questions in conservation. Which species deserve protection? How much should humans intervene in ecosystems they have already altered? Assisted migration does not introduce new ethical dilemmas so much as it forces decisions that conservationists have been avoiding.

Waiting for nature to “sort itself out” is not a neutral position. Climate change is a human-caused crisis, and letting species die without intervention is itself a moral decision. If entire ecosystems collapse because humans refused to act, that is not nature taking its course—it is inaction with consequences.

Could Assisted Migration Be Used as a Shortcut to Avoid Climate Action?

Some critics worry that governments and industries could use assisted migration as an excuse to delay reducing emissions. If species can be moved instead of protected, the argument goes, why bother tackling the root cause of the crisis?

This concern is valid, but it presents a false choice. Assisted migration is not a substitute for reducing carbon emissions. It is a response to damage already done. Even if emissions were cut to zero today, climate change will continue disrupting ecosystems for centuries.

The real danger is pretending that conservation strategies like assisted migration will be enough. They won’t. But they will buy time for species that would otherwise go extinct before larger solutions take effect.

The Bottom Line

Every approach to conservation carries risks. Keeping species in dying habitats guarantees their extinction. Moving them carries uncertainties but offers a chance for survival. The goal is not to relocate species carelessly but to develop careful, science-based strategies that balance risks with the urgent need for action.

The Future of Assisted Migration

Assisted migration has already moved from theory to reality. Scientists, conservationists, and land managers are moving species, restoring ecosystems, and experimenting with ways to help life survive a rapidly changing climate. But the future of assisted migration will require better data, new technologies, and stronger policies to guide these efforts at a larger scale.

The debate has already shifted. Instead of asking whether assisted migration should happen, the real challenge is figuring out how to do it effectively and responsibly.

Using Climate Models to Predict the Best Relocation Sites

Climate projections are improving. Researchers now use high-resolution models to identify future climate zones where species will be most likely to survive. These models incorporate temperature shifts, precipitation patterns, soil conditions, and ecological interactions, allowing conservationists to make better-informed decisions about where to relocate species.

Some projects have already put these models to use. Scientists planning the Monarch butterfly overwintering habitat relocation in Mexico are using climate forecasts to select high-altitude forests that will remain suitable for decades. Similar models are being applied to forest restoration, where species like the whitebark pine are being planted in areas expected to have stable conditions in the future.

As these models become more accurate, assisted migration will shift from reactive conservation to proactive planning. Instead of waiting for ecosystems to collapse, we can move species before their current habitat becomes unlivable.

Gene Banking and Assisted Evolution

For some species, relocation alone may not be enough. Scientists are turning to genetic conservation as another tool to help species adapt.

Seed banks and cryopreservation programs allow researchers to preserve genetic diversity, ensuring that species facing extinction can be revived or reintroduced later. Some seed banks, like the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, store thousands of plant species that may become essential for future reforestation or agriculture.

Other projects focus on assisted evolution—accelerating natural selection to help species adapt to new conditions. Coral researchers, for example, are breeding heat-resistant coral strains that can withstand rising ocean temperatures. These corals are now being planted in bleaching-prone reefs to help restore populations.

While genetic interventions remain controversial, they could provide critical support for species that are struggling to adapt fast enough.

Expanding Assisted Migration Beyond Individual Species

Most assisted migration projects today focus on moving a single species at a time, but ecosystems are more than individual organisms. The future of assisted migration will likely involve moving entire ecological communities—groups of species that depend on each other for survival.

The Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative is one early example. This project connects wildlife corridors across North America, allowing species like grizzly bears, lynx, and wolverines to migrate freely across landscapes as climate conditions shift. Rather than relocating animals directly, the goal is to restore movement pathways, helping ecosystems migrate on their own.

Some researchers propose going even further—actively transplanting pollinators, fungi, and soil microbes alongside plants and animals to recreate fully functional ecosystems. These efforts could help maintain species interactions that would otherwise be lost during migration.

Policy, Law, and International Cooperation for Assisted Migration

Conservation laws weren’t built for a climate-disrupted world, where species need to move far beyond historical ranges to survive. In the U.S., the Endangered Species Act (ESA) didn’t explicitly ban assisted migration, but a 1984 rule restricted “experimental populations” to areas within or near their native range. That made climate-driven relocations hard to justify legally, even when survival depended on moving species into entirely new regions.

In 2023, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed the historical range requirement, officially allowing assisted migration for federally listed species. The agency acknowledged that when the ESA was written, climate change wasn’t on the radar. Today, survival depends on moving species where conditions still work.

But species don’t stop at national borders, and that’s where things get even trickier. When species shift into new countries, they often lose legal protection, because most laws assume species stay in static ranges. Some agreements, like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, allow cross-border cooperation for certain species. But most plants, amphibians, and terrestrial species have no such safety net.

Projects like Yellowstone to Yukon (Y2Y) are creating corridors to help species move naturally between the U.S. and Canada, but they don’t authorize active assisted migration. To make climate-driven relocations work at scale, governments will need new agreements to let species cross borders into climate-safe habitats.

Without that cooperation, species could face regulatory roadblocks, even with suitable habitat just across the line. Climate change doesn’t respect borders, and assisted migration won’t work if we treat species like they do.

The Role of Public Involvement

Assisted migration will not be managed solely by scientists. Citizen-led projects like the Torreya Guardians, who relocated the endangered Florida torreya tree despite opposition from government agencies, show that public involvement can push conservation efforts forward when official channels move too slowly.

Urban and rural landowners are also becoming part of the solution. Programs that encourage individuals to plant climate-resilient species, create wildlife corridors, or participate in assisted migration experiments could expand conservation efforts beyond government agencies and research institutions.

If assisted migration is to succeed, it must become a shared effort, with scientists, policymakers, and the public working together to support species survival.

The Bottom Line

The future of assisted migration will be defined by better science, stronger policies, and broader public participation. As climate change accelerates, so must our efforts to help species adapt.

Long-Term Implications and Final Thoughts

Assisted migration is no longer a question of if—it is already shaping conservation efforts worldwide. As climate change forces species into crisis, relocation offers a chance to prevent extinctions and preserve ecological functions. But this strategy raises big questions about the future of conservation and human intervention in nature.

If assisted migration succeeds, it could redefine how we manage ecosystems in a warming world. If it fails, it could serve as a warning about the limits of intervention. Either way, the decisions made today will have consequences for centuries to come.

What Does Success Look Like?

The goal of assisted migration is to establish self-sustaining species populations that integrate into their new ecosystems. The best outcomes allow species to flourish alongside existing biodiversity, filling ecological roles without overwhelming native species or disrupting the balance of the new habitat.

Success would also mean that assisted migration becomes a proactive strategy. Instead of waiting for species to collapse before intervening, conservationists would move them before they reach the brink of extinction. Climate modeling, genetic research, and long-term monitoring will be key to making this approach work at scale.

Moreover success includes ensuring that ecosystems remain functional and resilient, even as climate conditions shift. If species move without destabilizing their new environments, assisted migration will have proven to be a valuable conservation tool.

What Happens If Assisted Migration Fails?

Not every relocation will work. Some species will struggle to adapt, while others might fail to establish in new locations. Even well-planned projects could unintentionally disrupt local ecosystems or fail to prevent extinction in the long run.

But failure does not mean assisted migration should be abandoned. Every attempt adds to our understanding of species movement, adaptation, and ecosystem resilience. The lessons learned from unsuccessful relocations can improve future efforts, making them more precise and effective.

The real failure would be refusing to act, allowing species to disappear without even attempting to help them survive. The cost of inaction is irreversible biodiversity loss—an outcome far worse than the risk of a failed relocation.

Will Assisted Migration Become the New Conservation Norm?

If climate change continues to accelerate, assisted migration could become a permanent feature of conservation. In the past, conservation efforts focused on protecting ecosystems where they existed. In the future, conservation may involve actively managing species movements, adjusting habitats, and even engineering ecosystems to maintain biodiversity.

Some researchers argue that we are already in a new era of conservation—one where preserving historical ecosystems is no longer possible. Instead of trying to keep nature the same, conservationists may need to shape it for the future, helping species relocate and adapt in ways that allow ecosystems to remain productive.

This shift will require a rethinking of conservation laws, funding priorities, and scientific research. It will also require societies to accept that human intervention in nature is now unavoidable.

The Role of Ethics in Future Decisions

Assisted migration raises ethical questions that will only become more complex as projects scale up. Who decides which species get relocated? Should resources go to species with the best survival chances or to those most at risk? Is it ethical to relocate species if it could cause unintended ecological disruptions?

There are no simple answers, but waiting for perfect solutions is not an option. Ethical conservation means making the best decisions possible with the knowledge available, refining strategies over time, and prioritizing both species survival and ecological balance.

Conclusion: A New Era of Conservation

Assisted migration forces us to confront a reality that many conservationists have resisted: nature will not return to what it was. Climate change has already reshaped ecosystems, severed ancient migration routes, and pushed species into survival mode. The debate over whether to intervene has already been settled. What matters now is whether we can act wisely, decisively, and fast enough to make a real difference.

For centuries, conservation has been about preservation—keeping species and landscapes intact. But the future of conservation may be about movement and adaptation. Instead of protecting static ecosystems, we may have to shepherd species across an unstable planet, guiding life toward the places where it can still persist.

This will not be a one-time effort. Assisted migration, if done right, becomes a long-term strategy for maintaining biodiversity in a world that will never stop changing. Species have always adapted, evolved, and moved, but never at the speed that climate change now demands. If we want to prevent the worst extinctions, we will have to move with them.

For some, this shift will feel like giving up—an admission that we can no longer save nature as it was. However, assisted migration represents a recognition that we caused the crisis, and now it’s on us to make sure life still has a place in the world we’ve changed.

Be sure to visit bleedingedgebiology.com next week for another “bleeding edge” topic!

Your Thoughts

Assisted migration challenges traditional conservation thinking. It forces us to ask how much we should intervene in nature, whether relocation is a necessary adaptation or an ecological gamble, and what responsibilities we have to species struggling to survive.

What do you think?

- Should we be moving species to help them escape climate change, or are the risks too high?

- Are there specific assisted migration projects you support or find concerning?

- Do you believe conservation should focus on preserving historical ecosystems or helping nature adapt to new realities?

I’d love to hear your thoughts! Drop a comment below and join the discussion.

Additional Materials

For those interested in exploring assisted migration further, here are some valuable resources:

Books

“Conservation Translocations”. Edited by Martin J. Gaywood, et al. CUP 2022 This volume draws on the latest research and experience of specialists from around the world to help provide guidance on best practice and to promote thinking over how conservation translocations can continue to be developed. The key concepts cover project planning, biological and social factors influencing the efficacy of translocations, and how to deal with complex decision-making.

Articles

Twardek, William M., et al. “The application of assisted migration as a climate change adaptation tactic: an evidence map and synthesis.” Biological Conservation 280 (2023): 109932. Mapped examples of where assisted migration has been implemented around the world. Although still infrequent, assisted migration was most common for plants (particularly trees), followed by birds, and rarely implemented other taxa.

Chen, Zhongqi, et al. “Applying genomics in assisted migration under climate change: Framework, empirical applications, and case studies.” Evolutionary Applications 15.1 (2022): 3-21. This paper explores how genomic approaches can enhance assisted migration efforts, ensuring the survival of species threatened by rapidly changing climates.

“Assisted Migration Helps Animals Adapt to Climate Change” By Joanna Thompson Sierra 2023. This article discusses the practice of assisted migration. It highlights the challenges and considerations of this controversial strategy.

“Playing the Hand of God: Scientists’ Experiment Aims to Help Trees Survive Climate Change” This article from The Guardian discusses scientists’ use of assisted migration—planting seedlings in new areas—to help tree species survive amid changing climates.

“Can We Move Our Forests in Time to Save Them?” By Lauren Markham, Mother Jones Dec 2021 Trees have always migrated to survive. But now they need our help to avoid climate catastrophe.

TED Talks/ Documentaries

“The Side of Climate Change We Are Not Debating Enough: How to Adapt” by Jessica Hellmann

In this talk, Jessica Hellmann discusses the necessity of adaptation strategies, including assisted migration, to address the impacts of climate change on biodiversity.

“Assisted Tree Migration and Its Potential Role in Adapting Forests to Climate Change” by Catherine Ste-Marie

This presentation delves into how assisted migration can help forest ecosystems adapt to changing climatic conditions.

“ The Mesquite Mile”, Kim Karlsrud et al. Commonstudio. Employs an assisted migration approach for the purpose of urban afforestation. In this work, focuses on a single iconic species: the Honey Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa).

“Coast Redwoods – assisted migration” Ghostsofevolution (11 total videos) – California’s two native species of redwoods have been thriving in horticultural plantings in the Pacific Northwest for more than a century. Connie Barlow documented a number of these plantings as grounds for advocating “assisted migration” poleward for “climate adaptation” of forests in coastal Washington state — and to ensure the two tree species will survive ongoing climate change.

Websites

USDA Forest Service: Assisted Migration

This resource from the U.S. Forest Service’s Climate Change Resource Center provides an overview of assisted migration, discussing its role in forest management and conservation strategies.

Center for Resilient Conservation Science: Assisted Migration

Hosted by The Nature Conservancy, this page delves into the intentional translocation of species or genetic material to more suitable habitats, offering insights into current projects and methodologies.

Yale Environment 360: Moving Endangered Species in Order to Save Them

This article examines the complexities and debates surrounding assisted migration as a conservation tool in response to climate change.

“Assisted Migration: A Primer for Reforestation and Restoration Decision Makers“

This compilation features presentations from leading professionals discussing assisted migration strategies. The symposium was held in Portland, Oregon, at the World Forestry Center on February 21, 2013, and was sponsored by the USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station, the University of Idaho, and the Western Forestry and Conservation Association.